Free E-Mail

Bible Studies

Beginning the Journey (for new Christians). en Español

Old Testament

Abraham

Jacob

Moses

Joshua

Gideon

David, Life of

Elijah

Psalms

Solomon

Songs of Ascent (Ps 120-135)

Isaiah

Advent/Messianic Scriptures

Daniel

Rebuild & Renew: Post-Exilic Books

Gospels

Christmas Incarnation

(Mt, Lk)

Sermon on the Mount

(Mt 5-7)

Mark

Luke's

Gospel

John's Gospel

7 Last Words of Christ

Parables

Jesus and the Kingdom

Resurrection

Apostle Peter

Acts

The Early Church

(Acts 1-12)

Apostle Paul

(Acts 12-28)

Paul's Epistles

Christ Powered Life (Rom 5-8)

1 Corinthians

2 Corinthians

Galatians

Ephesians

Vision for Church

(Eph)

Philippians

Colossians,

Philemon

1

& 2 Thessalonians

1 & 2 Timothy,

Titus

General Epistles

Hebrews

James

1 Peter

2 Peter, Jude

1, 2, and 3 John

Revelation

Revelation

Conquering Lamb of Revelation

Topical

Glorious Kingdom, The

Grace

Great Prayers

Holy Spirit, Disciple's Guide

Humility

Lamb of God

Listening for God's Voice

Lord's Supper

Names of God

Names of Jesus

Christian Art

About Us

Podcasts

Contact Us

Dr. Wilson's Books

Donations

Watercolors

Sitemap

James J. Tissot, 'St. John the Evangelist' (1886-94) gouache on paper, 13.6x9.7". Brooklyn Museum, New York. |

John's Gospel is dramatically different than the Synoptic Gospels (meaning similar Gospels, "presenting the same view") -- Matthew, Mark, and Luke. These first three Gospels share, to some degree, a similar source, and often have passages that seem almost the same word-for-word as in the others.

But John's Gospel is in a class by itself. It draws upon a separate, independent gospel tradition. It's as if the Synoptic Gospels tell the story of Jesus' life, miracles, parables, and teaching, letting readers draw their own conclusions. But John is very selective in the events he includes. And when he does include a miracle, he often leads us to ponder its meaning in a discourse. John's Gospel, written late in the apostle's life, is full of thoughtful, theological reflection.[1]

John Calvin said about the four Gospels:

"As all of them had the same object in view, to point out Christ, the three former exhibit his body, if we may be permitted to use the expression, but John exhibits his soul."[2]

A great deal has been written about John's Gospel, for it is deep and complex for the scholar. For a more thorough introduction, consult one of the technical commentaries. However, here are some of the basics that will help you as you begin to study.

Authorship

The nearly unanimous tradition of the early church is that John the Apostle, son of Zebedee, is the author of the Gospel that bears his name. The first clear reference is by Irenaeus (died 202 AD). Irenaeus knew personally Polycarp (69 to c. 160 AD), who in turn had been a personal disciple of the Apostle John. Irenaeus wrote:

"John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia."[3]

Eusebius quotes Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215 AD) as saying:

"But John, last of all, conscious that the outward facts had been set forth in the Gospels, was urged on by his disciples, and, divinely moved by the Spirit, composed a spiritual gospel."[4]

I could go on. By the end of the second century AD there is virtual agreement in the Church as to the authority, canonicity, and authorship of the Gospel of John.

This remained so until the mid-nineteenth century, the rise of the Enlightenment. The question of whether the Apostle John was the author of this Gospel has raged hot in the twentieth century. Many place its authorship within the "Johannine Community," written perhaps by a disciple of John.

However, I believe there are strong reasons to accept John the Apostle, son of Zebedee, as the author of the Gospel of John. Chief of these is the testimony of an editor at the end of the Gospel itself about "the disciple that Jesus loved."

"Peter turned and saw that the disciple whom Jesus loved[5] was following them. (This was the one who had leaned back against Jesus at the supper and had said, 'Lord, who is going to betray you?') ... This is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true." (21:20, 24)

It is clear that this Beloved Disciple was close to Jesus (13:23, 24), trusted by Jesus with the care of his mother (19:26-27), was the only disciple who remained at the cross when Jesus died (19:34-35), the disciple who raced Peter to the tomb (20:2-5, 8), and the one who recognized Jesus on the shore after the resurrection (21:7). It is the Beloved Disciple who Jesus hinted might outlive St. Peter (21:20ff). Of course, the term "the disciple that Jesus loved," is a strange way to indentify oneself. But it is also a strange way to identify someone else! There are clear evidences of eyewitness testimony, and much more.

From both external sources and internal evidence, the strongest case can be made for John as the author of this Gospel. The case for any other author is much weaker.

Date and Place

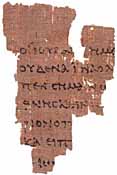

|

|

So John is the author. But when and where was the Gospel written? While there is little evidence, most scholars see the date of John's Gospel as comparatively late, probably in the 90s AD, though some evangelical scholars see it as written somewhat earlier.[6]

John's Gospel can't have been written much later than 100 AD. The earliest known fragment of a New Testament document is Papyrus 52, from Egypt dating from about 130 AD. It contains portions of John 18:31-33. Other early portions of John come from the second century AD (Papyri 66 and 75) and the early third century (Papyrus 45).

The 90s AD is considerably later than the proposed date for Mark, usually seen as the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels, written probably in the 60s AD. John seems to assume that his readers are acquainted with the facts of Jesus as given in the Synoptic Gospels (1:40; 3:24; 4:44; 6:67, 71; 11:1-2).

There are several early traditions that place the Apostle John as Bishop of Ephesus. Revelation 1:9 places John, author of Revelation, in exile on the Island of Patmos, off the coast of Asia Minor near Ephesus. Irenaeus (cited above) refers to John's residence in Ephesus.[7] Justin Martyr (in 135 AD) places John at Ephesus.[8] While there, John probably penned his Gospel.

Purpose

While many reasons have been suggested for why John wrote his Gospel, the most straightforward is the purpose stated in the Gospel itself:

"Jesus did many other miraculous signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name." (John 20:30-31)

While the Synoptics give many more incidents in Jesus' life, and the instruction of many parables and sayings, John seems to have an evangelistic purpose that guides his selection of material. He wants his readers to be convinced that Jesus is the promised Messiah and the divine Son of God, to the end that they might experience his Life. Perhaps this is why John is a favorite gospel to give to inquirers and new Christians.

John probably wrote to convince unbelieving Greek-speaking Jews to believe in Jesus as the Christ, the Messiah. But since he often explains Jewish customs in Palestine, he probably has Gentile unbelievers in mind as well.

John and the Synoptics

It seems clear that while John was aware of the Synoptic Gospels, there is no evidence of literary dependence upon them. John represents a unique, eyewitness gospel tradition.

There are, of course, some similarities between John and the Synoptics -- they all focus on the life of Jesus of Nazareth -- but there are many differences. For example, John tends to:

- Record longer discourses, rather than parables and brief sayings.

- A focus on eternal life more than on the Kingdom of God.

- Fewer miracles, but an emphasis on them as "signs" of who Jesus is.[9]

- A strongly theological prologue, that begins by telling us just who Jesus is.

- No Christian baptism or sacraments mentioned.

- Ministry primarily in Judea and Jerusalem, with less on his Galilean ministry.

- A focus on Jewish feasts, especially on the Passover.

- An emphasis on the tragedy of Jesus' rejection by his own people and their leaders.

Theology

John is an intensely theological book. Some of the strongest themes include:

- The Word/Logos.

- God as Father.

- The "I Am" sayings.[10]

- Jesus as Son of God.

- Jesus as the Christ.

- Miracle signs and their relationship to true faith.

- Salvation.

- Life -- especially eternal life.

- The Holy Spirit as Paraclete.

We'll be exploring these in the lessons to come.

Style

John's writing style is different. If you're especially observant, you may spot some of these characteristics:

- Quasi-poetic, solemn style of Jesus' discourses.

- Purposeful twofold or double meanings. For example, in 3:16 the Greek adverb anōthen can mean both "from above" and "again."

- Misunderstanding, where Jesus is speaking on the heavenly level, but he is misunderstood as speaking to a material or earthly situation. Examples: water and bread, his body as the temple.

- Irony. Derogatory statements of Jesus' enemies are often ironic in the sense that they say more than they know they are saying.

- Explanatory notes are common, to explain names, symbols, and customs to make sure readers in a different place and culture understand the references.

Summary

Many mature Christians find the Gospel of John to be their "favorite" Gospel, one that they go back to again and again. It is rich. It is cosmic in its view of the Christ. And it is convincing in its explanation of who Jesus is and what he has done for us.

John contains perhaps the most-often memorized verse in the entire Bible, loved by all because it seems to contain the scope of the Gospel in a single sentence.

"For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life." (3:16, ESV)

It is my prayer that by a deep study of John's Gospel your faith will be deepened, and that you will find many opportunities to point others to Christ, that they too might find eternal life.

Prayer

Father, thank you for this wonderful Gospel. I pray that you would help my brothers and sisters persist through the many lessons that comprise this study -- that they won't let circumstances force them to drop out and leave many passages unstudied and unappropriated for their lives. Enrich us as we study. May your Holy Spirit work within us as we study so that Christ may be formed in us. In Jesus' holy name we pray. Amen.

Endnotes

[1] This is not intended to deny that each of the Synoptic Gospel writers came from his own particular theological perspective and focus on a particular audience.

[2] John Calvin, Commentary on the Gospel of John, The Argument.

[3] Irenaeus, Against Heresies, xxx, 1, 2. There is a clear reference to the "beloved disciple" in John 13:23.

[4] Clement, quoted by Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, VI, xiv, 7. Cited by Carson, John, pp. 27-28.

[5] Based on John 11:3, some have presumed that Lazarus is to be understood here.

[6] Morris (John, p. 35), sees a date "prior to 70 AD," the fall of Jerusalem. Carson (John, p. 82) holds a tentative date of 80 AD.

[7] Irenaeus, Against Heresies, xxx, 1, 2.

[8] Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 81.4.

[9] See Appendix 5. "Signs" in John's Gospel.

[10] Appendix 4. The "I Am" Passages in John's Gospel.

Copyright © 2025, Ralph F. Wilson. <pastor![]() joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

|

|

In-depth Bible study books

You can purchase one of Dr. Wilson's complete Bible studies in PDF, Kindle, or paperback format -- currently 48 books in the JesusWalk Bible Study Series.

Old Testament

- Abraham, Faith of

- Jacob, Life of

- Moses the Reluctant Leader

- Joshua

- Gideon

- David, Life of

- Elijah

- Psalms

- Solomon

- Songs of Ascent (Psalms 120-134)

- Isaiah

- 28 Advent Scriptures (Messianic)

- Daniel

- Rebuild & Renew: Post-Exilic Books

Gospels

- Christmas Incarnation (Mt, Lk)

- Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5-7)

- Luke's Gospel

- John's Gospel

- Seven Last Words of Christ

- Parables

- Jesus and the Kingdom of God

- Resurrection and Easter Faith

- Apostle Peter

Acts

Pauline Epistles

- Romans 5-8 (Christ-Powered Life)

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Galatians

- Ephesians

- Philippians

- Colossians, Philemon

- 1 & 2 Thessalonians

- 1 &2 Timothy, Titus

General Epistles

Revelation

Topical