|

Old Testament

New Testament

Gospels

Acts

Paul's Letters

General Letters

Revelation

Topical Studies

Beginning the Journey (for new Christians). en Español

|

Old Testament

New Testament

Gospels

Acts

Paul's Letters

General Letters

Revelation

Topical Studies

|

Home

Bible Studies

Articles

Books

Podcasts

Search

Menu

Donate

About Us

Contact Us

FAQ

Sitemap

Before we begin our study of the great book of Isaiah, it's important to look at the book as a whole, to try to understand it in its own context. And we need to ask some general questions that underlie each of the chapters we'll be studying. Let's consider:

- The historical context of Isaiah's time

- The authorship of Isaiah

- The nature of Old Testament prophecy

The Historical Context of Isaiah's Time

If you're just getting familiar with the Old Testament, Isaiah's prophecies belong to the period of the Monarchy -- dates are only approximate.

- Patriarchs (1800-1500 BC)

- Exodus (1400 BC)

- Conquest and Judges (1400-950 BC)

- Monarchy (950 to 587 BC)

- Exile (604 to 537 BC)

- Return and Rebuilding (537 to 400 BC)

- Intertestamental period (400 BC to 6 BC)

- Life of Jesus of Nazareth (6 BC to 27 AD)

Specifically, Isaiah prophesied during the reign of four Judean kings, probably between about 750 to 700 BC or a bit later. We're not told what year he died.

Historical Context

Isaiah's prophecy is set in an historical context in the first verse.

"The vision concerning Judah and Jerusalem that Isaiah son of Amoz saw during the reigns of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah, kings of Judah." (1:1)

Here's a brief summary of the reigns of the kings who ruled during his ministry.

Uzziah / Azariah (reigned 783-742 BC; 2 Kings 15; 2 Chronicles 26)

|

|

Uzziah (sometimes called Azariah) was only sixteen when he was made king over the southern kingdom of Judah, following his father's assassination. His older contemporary, Jeroboam II (786-746) reigned over the northern kingdom of Israel. Both had long reigns, 41 and 42 years respectively, at a time when both Judah and Israel were at the zenith of their power. Under Jeroboam, Israel expanded its territory into Syria as far as Hamath, much like the northern reach of Solomon's realm. It was a very prosperous time for both kingdoms, which were at peace with each other.

Uzziah helped repair the defenses of Jerusalem, reorganized and refitted the army, and expanded Judah's control over the Edomite lands, all the way to Ezion-geber at the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba. He also controlled a number of Philistine cities -- Gath, Jabneh, and Ashdod.

Late in his reign, Uzziah was stricken with leprosy. He yielded the public exercise of power to his son Jotham, but seemed to be the power behind the throne as long as he lived.

Isaiah received his call to ministry in a vision he saw the year King Uzziah died, a vision of God on his throne (Isaiah 6).

The northern kingdom's long-reigning king, Jeroboam II, died a few years prior to Uzziah. At Jeroboam's death, his son Nadab reigned, only to be assassinated two years later. Over the next several years, one dynasty followed another. The northern kingdom was in anarchy, facing a growing threat from Assyria.

Jotham (co-regent 750, reigned 742-735 BC; 2 Kings 15; 2 Chronicles 27)

Uzziah's son Jotham served as co-regent while Uzziah suffered from leprosy, and took the throne when he died, reigning seven years during a very difficult time.

For centuries there had been no world power that threatened Judah or Israel. Yes, Egypt was a power to the south, and there were skirmishes with other neighbors. But no one power dominated the entire area. That was to change during Jotham's reign.

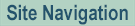

Having consolidated power in the east, Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III (745-727 BC) turned his attentions to the west. By 738, he had taken tribute from most of the states of Syria and northern Palestine. His campaigns were not tribute-gathering expeditions, but rather expeditions of permanent conquest. Kings would either become his vassals or, when they rebelled or resisted his armies, he would deport their leaders and incorporate their lands as provinces of the Assyrian empire.

Menahem, king of Israel from 745-737 BC, gave tribute to Tiglath-pileser and became a vassal state in order to survive. At this point, Jotham maintained an anti-Assyrian policy, but Assyrian troops were not yet threatening Judah as they were Israel.

Ahaz (co-regent 735, reigned 732-716 BC; 2 Kings 16-17; 2 Chronicles 28)

After Jotham died, his son Ahaz reigned from 732-716 BC, a terribly difficult time. Ahaz reversed his father's policy and became pro-Assyria. When Assyrian conqueror Tiglath-pileser was preoccupied stabilizing other areas of his empire, some of the conquered kingdoms rebelled. Pekah, king of Israel (737-732) joined Rezin, king of Damascus in an uprising. When Judah's king Ahaz refused to join the confederacy, Judah was invaded and Jerusalem attacked (2 Kings 16:5; 2 Chronicles 28:1-15). At this same time, the Edomites threw off Judean rule (2 Chronicles 28:17).

With his throne endangered, Ahaz appealed to Tiglath-pileser for aid -- and agreed to pay tribute and become his vassal. In order to pay the tribute demanded by Assyria, Ahaz was forced to empty his treasury and strip the temple (2 Kings 16:8, 17; 2 Chronicles 28:16-21). Tiglath-pileser destroyed Damascus in 733-32, and began to deport some of its population (2 Kings 15:29). Israel's last king, Hoshea (732-724), submitted to become Assyria's vassal at this time, but when Tiglath-pileser died in 727, Hoshea appealed to Egypt for help and withheld tribute -- an act of rebellion. Egypt, however, was too weak to help.

The Assyrian Empire during Isaiah's Ministry. Primary

source: Michael Roaf, Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near

East (FactsOnFile/Equinox, 1990), p. 179.

Larger map.

But Tiglath-pileser's son Shalmaneser V (726-722 BC) was not a weak leader. He and his successor, Sargon II (721-704 BC), responded by destroying Samaria in 721 BC and deporting 27,290 of its citizens to Upper Mesopotamia and Media, where they disappeared from the stage of history. Sargon also defeated an Egyptian force at Raphia in 720 BC. Then he resettled other peoples in Israel to replace the exiles. Their descendants became known as the Samaritans.

To appease his Assyrian overlord, King Ahaz of Judah began to open Israel to foreign gods, and constructed a bronze altar in the temple, a copy of an altar to an Assyrian god built in Damascus. As evidence of his departure from the worship of Yahweh, Ahaz even offered his own son as a pagan sacrifice (2 Kings 16:3).

"Ahaz gathered together the furnishings from the temple of God and took them away. He shut the doors of the LORD's temple and set up altars at every street corner in Jerusalem. In every town in Judah he built high places to burn sacrifices to other gods and provoked the LORD, the God of his fathers, to anger" (2 Chronicles 28:24-25).

Hezekiah (reigned 715-687 BC; 2 Kings 18-20; 2 Chronicles 29-32)

The final king that Isaiah the prophet ministered under is Hezekiah. He is probably co-regent with his father for several years. Hezekiah is 25 when he begins to reign on his own in 715 BC, and he reigns for 29 years until about 687 BC, a long period.

During the first part of Hezekiah's reign, the Assyrian threat has diminished. In 720 BC, Sargon's attention is diverted when he is forced to quell rebellions close to home, in Babylon, Carchemish in Syria, and then Uratu, to Assyria's north.

At the same time that Assyria's influence is weakening, Egypt's influence is growing. Pharaoh Piankhi, founder of the Twenty-fifth (Ethiopian) Dynasty, encourages some of the Philistine cities to rebel against Assyria to create a buffer between Assyria and Egypt. In 712 BC, Sargon's army returns and crushes the rebel Palestinian states -- though not Judah.

In the meantime, Hezekiah is hard at work reversing his father Ahaz's pagan policies. He brings about great religious reforms, turning people away from idolatry and returning them to Yahweh in a great revival. He also brings relief to economic abuses that have been oppressing the poor.

As long as Sargon lives, Hezekiah makes no break with Assyria. But when Sargon's son Sennacherib (704-681) succeeds him, Hezekiah rebels. Sennacherib is preoccupied by rebellions in Babylon and Elam. At the same time, Tyre and other Phoenician cities join the rebellion, along with Philistine cities Ashkelon and Ekron, as well as Moab, Edom, and Ammon. Hezekiah sends envoys to Egypt to negotiate a treaty. He also shores up Jerusalem's defenses (2 Chronicles 32:3-5) and constructs the famous Siloam tunnel to ensure a water supply for Jerusalem in case of siege (2 Kings 20:20).

When Sennacherib has pacified Babylon and other nearby states, however, he moves back to Palestine, moving southward along the coast in 701 BC. One after another, kingdoms topple or hasten to pay tribute. Sennacherib attacked 46 of Judah's fortified cities and threatened Jerusalem. Some of this campaign is chronicled on massive friezes now on display at the British Museum, including the siege of Lachish.

Realizing his hopeless situation, Hezekiah sues for peace, paying a huge tribute that requires him to strip the temple and raid his own treasury. Some of his own daughters are sent to Nineveh as concubines. Sennacherib seems to regret not destroying Jerusalem. Now his troops move to Jerusalem demanding surrender. Isaiah advises Hezekiah to resist. Finally, Sennacherib's army is hit by an epidemic and returns home leaving Jerusalem unharmed.

At some point, Hezekiah entertains an envoy from Babylon, showing them his nation's wealth. He dies in 687/6 BC, a great king with great faith in Yahweh. (For more on Hezekiah, see Lesson 6.) His son Manasseh, turned out to be an apostate. Manasseh eventually gives up the rebellion and makes peace with Assyria.

Kings of Judah during Isaiah's Ministry

The whole period is confusing. To help you comprehend this data, I've prepared a table comparing the rulers of Judah, Israel, Assyria, and Egypt during Isaiah's lifetime.

| Judah | Israel | Assyria | Egypt |

|

Uzziah (783-742) Prophet Isaiah |

Jeroboam II (786-746) Zechariah 746-745 |

|

22nd Dynasty (ca. 935-725) |

|

23rd Dynasty (ca. 759-715)

24th Dynasty) | |||

|

Jotham |

Shallum (745) Menahem (745-737) Pekahiah (737-736)

|

Tiglath-pileser III (745-727) |

|

|

Ahaz |

Pekah (736-732) Hoshea (732-724) Fall of Samaria (722/1) |

Shalmaneser V (726-722) Sargon II (721-705)

|

25th Dynasty (Ethiopian, ca. 725-664 BC) Shabako (ca. 710/9 to 696/5) Tirhaka (690 to 664) |

|

Hezekiah |

|

Sennacherib (704-681, invades in 701) |

For your convenience, I've also summarized this period in Appendix 4. Timeline Related to Isaiah's Prophecies

Old Testament Prophets

Isaiah is called a prophet (37:2; 38:1; 39:3-4). The word is nābîʾ, of uncertain derivation.[1] An Old Testament prophet was "a spokesperson for God who announced God's will or intentions for people, or predicted the future, or did both."[2] The prophetic tradition began with Abraham and Moses, continued through the prophets of the monarchy (David, Nathan, Isaiah, Jeremiah, etc.) and the Exile (Jeremiah, Ezekiel), and the Restoration (Zechariah, etc.), and continued through John the Baptist. We also find a gift of prophecy and prophets in the New Testament Church.

Forthteller. Some scholars have emphasized that prophets were "forthtellers," that is, proclaimers of God's message. Certainly, Isaiah was that. Much of his prophecy was a pronouncement of God's judgment on sin, a call for justice and righteousness by those in power, and a concern for the poor. Some prophecies encouraged kings and pointed to wise policies to guide the nation of Judah.

Foreteller. Some prophets were also "foretellers," that is, they brought predictions of the future. Isaiah's earlier prophecies concern the short-term future of Judah and the surrounding nations. But most of the prophecies in chapters 40 to 66 foretell and speak to situations centuries (and millennia) in advance. For example, Isaiah foresaw the Babylonian exile, the Jew's deliverance from exile by Cyrus the Great, as well as the reign of the Messiah and the New Heavens and the New Earth.

Unlike some prophets who were poor farmers, Isaiah seems to be called from one of the elite families of Judah. He is called the son of Amoz. Rabbinic tradition states that he was a member of the royal family and a cousin of King Uzziah[3]. If true, this would explain why he was able to utter strong prophecies directing political policy without being persecuted. Apparently he ministered primarily in and around Jerusalem, the capital city of the Kingdom of Judah.

His wife is designated as "the prophetess" (8:3). Isaiah had two sons we are told of, each with a symbolic name. Micah was also a prophet in Judah about the same time as Isaiah (Micah 1:1). Amos seemed to have preceded Isaiah as a prophet in Judah by a few years (Amos 1:1).

Though he was from a prominent family and had access to the royal household, Isaiah didn't dress like a noble. Apparently, he wore sandals and was probably dressed in a garment of sackcloth (a sign of humility and mourning), except for a three-year period during which his prophetic garb was discarded (20:2-6). Material used to make sacks for grain were coarse, made of goat or camel hair.[4] Isaiah's predecessor Elijah wore "a garment of hair and ... a leather belt around his waist" (2 Kings 1:8; cf. Zechariah 13:4), as did John the Baptist (Matthew 3:4).

Interpretation of Prophecy

One of the issues we will encounter in Isaiah is how to interpret his prophecies.

Direct fulfillment. Most of Isaiah's prophecies have a direct fulfillment. For example, Isaiah predicted the fall of both Israel and Syria (7:7) and that Jerusalem would not fall to the Assyrian armies (37:6), both of which were fulfilled in Isaiah's lifetime. He also prophesied future events that he did not live to see -- the Babylonian exile (39:5-7) and Babylonia's fall to Cyrus II (44:28; 45:1, 13).

Double Fulfillment. But we also see prophecies that seem to have a double fulfillment (though this is denied by some Bible interpreters). For example, Isaiah's prophecy about a virgin conceiving a son named Immanuel was apparently fulfilled in Isaiah's lifetime and in the birth of Jesus the Messiah. Isaiah's prophecy about the restoration of Jerusalem after the exile was fulfilled historically in 537 to 520 BC, but also seems to point beyond to a perfect Jerusalem in the Last Days (65:17-25). Isaiah had a vision of the Messiah (John 12:41) and of the New Heavens and the New Earth (65-66), but he saw them through the context of events near to his own time, as if they were part of a mountain range visible beyond one close by, with no indication of the distance between the near and the far. We need to be careful that we don't impose our own interpretations on Isaiah's prophecies, but seek the guidance of the apostles and the Book of Revelation as we seek to understand their fulfillments.

The Authorship of Isaiah

"Who wrote the Book of Isaiah?" may seem a stupid question, something like, "Who's buried in Grant's tomb?" But it's a question that has created a lot of controversy. A careful reader will observe three different sections of Isaiah. In the past, some people referred to these as First, Second, and Third Isaiah (though I don't think these titles are very helpful, and most scholars are moving away from these designations).

- Chapters 1-39. Prophecies concerning contemporary events within Isaiah's lifetime.

- Chapters 40-55. Prophecies directed toward people during an exile (which took place in Babylon about 609-537 BC). The deliverer Cyrus is named in 44:28 and 45:1, and obviously refers to a Persian ruler (reigned 559-530 BC) who united the Medes and the Persians, and conquered Babylon in 539 BC, perhaps 150 years after Isaiah.

- Chapters 56-66. Prophecies that describe the period of the restoration of Jerusalem (537-520 BC), perhaps 200 years after Isaiah, and the New Heavens and New Earth, which has yet to be fulfilled.

Many conservatives and evangelicals (including myself) believe Isaiah of Jerusalem to be the author of the book, perhaps subject to some later editing. Other scholars give several reasons to support multiple authorship: [5]

- Predictive prophecy is impossible. Usually unsaid, but clearly underlying some scholars, is the philosophical assumption that predictive prophecy is not possible, so that there must be another explanation.[6] This parallels a seeming necessity by some to explain away miracles in the New Testament, for example, because of a philosophical assumption that miracles can't really happen.

- Varied settings. The setting presupposed in different parts of the book varies considerably.

- Diversity of messages. The messages of the different parts of the book are so diverse that they cannot be understood as other than accompanying historical change.

- Style and vocabulary changes. A radical change in style occurs between chapters 1-39 and chapters 40-66, the latter being more lyrical and exalted.

- Form of address. Other prophets, when predicting the future, do not seem to address their words to people in the future, as does Isaiah.

- Claim of Isaiah's authorship is found several times in chapters 1-39, but not in chapters 40-66.

For each of these supposed reasons for multiple authorship there are excellent responses. Briefly, conservatives argue:

- Predictive prophecy is used by Isaiah himself to prove the veracity of his message (42:9; 44:7-8; 46:10). To deny the validity of predictive prophecy and miracles is a philosophical assumption that is foreign to the Bible. You find predictive prophecy within chapters 1 through 39, as well as in chapters 40 to 66.

- New Testament references to Isaiah all assume that Isaiah of Jerusalem was the author.[7]

- Style changes in Isaiah can be explained by the different types of literature. Most of the earlier contemporary prophecies were probably transcriptions of sermons, while prophecies of the future were probably in written form.

- Other prophets also gave messages intended to be read by people at a future time. Setting changes would be expected with this type of prophecy.

- Isaiah's contemporary prophecies bear historical and geographical clues that signify an eyewitness, while his prophecies for a future time do not bear such eyewitness indications -- just what you'd expect if chapters 40-66 were authored by Isaiah of Jerusalem a century or more before they were needed.

My conclusion is that Isaiah's huge body of prophecies are indeed remarkable and diverse, but well within the scope of an inspired prophet's ministry extending over perhaps 25 to 50 years. The book is admittedly complex. But I believe that the unity of the book authored by Isaiah of Jerusalem explains the book better than assigning authorship to multiple authors or "schools" of the prophet that wrote beyond Isaiah's lifetime.

Characteristics of Hebrew Poetry

With a few exceptions, Isaiah's prophecy is couched in Hebrew poetry. Hebrew poetry differs from most Western poetry in that it doesn't rhyme. To appreciate what you are reading, you need to understand what characterizes this kind of Hebrew literature. There seem to be three primary elements:

- Thought parallelism

- Imagery

- Meter

From the English Bible we have no way of assessing the sound and rhythm of Hebrew phraseology, so we won't be discussing that here.

In western poetry we use both rhyme and rhythm in traditional poems. But in Hebrew poetry the rhythm may be in terms of units per line. However, the exact nature of this is still debated and some recent scholars have concluded that the poetic portions are not metrical, that this is an idea imported from Western poetical forms. Longman recommends caution about any interpretation based primarily on a verse's supposed meter.[8] But two elements can be easily discerned by a reader of the English Bible.

1. Thought Parallelism

The element of thought parallelism in Hebrew poetry is quite apparent and has become better understood in recent decades. Unlike poetry that relies on rhyme, parallelism can be translated into other languages without losing its distinct flavor. The two basic types of parallelism are synonymous parallelism and antithetical parallelism.

Synonymous Parallelism is the most common form. Here the idea of the first line is reinforced in the second line:

"They will beat their swords into plowshares

and their spears into pruning hooks." (2:4b)

You can find parallelism in Jesus'teaching, too (for example, Matthew 5:43-45). But scholars have realized rather recently that synonymous parallelism is something of a misnomer. The lines are not strictly synonymous. You might describe it as "A, what's more B." The second line always seems to carry forward the thought found in the first phrase in some way. This progression is sometimes subtle, but often quite obvious. The second -- or sometimes third line -- reinforces and extends the meaning of the first, like a second wave that mounts higher than the first, and a third even higher yet, such as in 11:6.

"The wolf will live with the lamb,

the leopard will lie down with the goat,

the calf and the lion and the yearling together;

and a little child will

lead them."

When interpreting Hebrew poetry, however, it's important not to overemphasize the nuances between the similar words, for example, between "plowshares" and "pruning hooks" in 2:4b. As Kidner puts it, "They are in double harness, rather than in competition."[9] Rather look for the ways that second idea builds upon the first.

Antithetic Parallelism is also common. The idea in the first line is contrasted or negated in the second line as a means of reinforcing it.

"Though your sins are like scarlet,

they shall be as white as snow;

though they are red as crimson,

they shall be like wool." (1:18)

In addition to these two common forms of Hebrew parallelism, scholars have found a number of other less prominent varieties. Hebrew poetry was a fine art that we are just beginning to appreciate more fully.

2. Imagery

A second common characteristic of Hebrew poetry is its use of imagery, comparing one thing to another. Of course, imagery can be found in prose sections of the Old Testament, but it is especially rich in Hebrew poetry. Imagery has a way of fixing an idea in our minds with clarity.

Think about the images in the passage describing the extent of the Messianic peace:

"The wolf will live with the lamb,

the leopard will lie down with the goat,

the calf and the lion and the yearling together;

and a little child will lead them.

The cow will feed with the bear,

their young will lie down together,

and the lion will eat straw like the ox.

The infant will play near the hole of the cobra,

and the young child put his hand into the viper's nest.

They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain,

for the earth will be full of the knowledge of the LORD

as the waters cover the sea." (11:6-9)

In prose we might say with some accuracy: "There will be complete peace and absence of conflict." It is true, but not particularly memorable. The power and beauty of this passage is the way that it communicates these ideas through images: wolves and leopards living peaceably with their natural victims -- lambs and goats. These images in our minds, with the thoughts and emotions they evoke, contribute to make this passage a favorite.

There are two kinds of images used in Isaiah:

"He tends his flock

like a shepherd:

He gathers the lambs in his arms

and carries them close to his heart." (40:11)

"Surely the nations

are like a drop in a bucket;

they are regarded as dust on the scales;

he weighs the islands as though they were fine dust." (40:15)

"I will make

justice the measuring line

and righteousness the plumb line." (28:17a)

A metaphor communicates a more vivid image than a simile because it is implicit and draws the comparison more closely. As you study Isaiah, be aware of the images that are used and the thoughts and emotions that they are intended to evoke in us, the readers.

Isaiah's High Literary Style

As you read Isaiah, read for meaning and comprehension. That's a given. But don't stop there. Read it also to enjoy the highest literary style in the entire Bible, literature that is considered world-class nearly 3,000 years later. George L. Robinson said, "For versatility of expression and brilliance of imagery Isaiah had no superior, not even a rival."[10]

You'll find in Isaiah some of the most beautiful literature in the history of man. Here are a few passages of the many in Isaiah that reach such heights:

- 1:18-20 -- "Come, let us reason together"

- 5:1-7 -- The Song of the Vineyard

- 6:1-8 -- Isaiah's Call

- 9:2-7 -- "Unto us a child is born...."

- 11:1-9 -- The peace of the Messiah who rises from Jesse's stump

- 35:1-10 -- The Highway of Holiness

- 40:1-31 -- "Comfort, comfort my people...."

- 45:5-10 -- "Woe to him who quarrels with his Maker...."

- 52:13-53:12 -- "By his wounds we are healed...."

- 55:1-12 -- "Come, all you who are thirsty...."

- 58:1-14 -- "Is not this the kind of fasting I have chosen....?

- 61:1-11 - "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me...."

End Notes

[1] There are four theories of the derivation of nābîʾ: (1) From Arabic root, nabaʾa, "to announce," hence "spokesman." (2) From a Hebrew root, nābāʾ, softened from nābaʿ, "to bubble up," hence pour forth words, perhaps ecstatically. (3) From an Akkadian root nabû, "to call," hence one who is called [by God] (Albright, Rowley, Meek, Scott), hence one who felt called of God. (4) From an unknown Semitic root. I think it is safer not to assume a derivation for the word and build a theory of its meaning from this speculation. Rather the meaning should be derived from its usage in the Old Testament. (Robert D. Culver, TWOT #1277).

[2] Paul L. Redditt, "Prophecy, History of," DOTP, p. 587.

[3] According to the Rabbinic literature, Isaiah was a descendant of the royal house of Judah and Tamar (Sotah 10b). Isaiah was the son of Amoz, who was the brother of King Amaziah of Judah, this would make Isaiah and King Uzziah cousins (Talmud tractate Megillah 10b).

[4] Larry G. Herr, "Sackcloth," ISBE 4:256. Our English word "sackcloth" comes from the Hebrew word śaq, "sackcloth, sack."

[5] Several of these arguments are defended by evangelical scholar H.G.M. Williamson, "Isaiah: Book of," DOTP, 364-378. Good defenses to these arguments are discussed in Oswalt, Isaiah 1-39, pp. 23-28; Isaiah 40-66, pp. 3-6; Motyer, Isaiah, pp. 31-38; Young, Isaiah, vol. 3, pp. 538-549.

[6] Williamson disagrees. "This conclusion has nothing to do with belief or not in the power of predictive prophecy; after all, there is still predictive prophecy included in all parts of the book even on the most radical of critical positions" (R.G.M. Williamson, "Isaiah, Book of," DOTP, p. 370). I'm not convinced. Most of those who don't believe in the unity of Isaiah allow that Isaiah contains predictive prophecy, but don't believe that God necessary will fulfill these predictive prophecies.

[7] However, according to evangelical scholar H.G.M. Williamson, New Testament references to Isaiah may be perfectly well understood as a reference to the book, not to the author (except John 12:41) ("Isaiah: Book of," DOTP, 364-378).

[8] Tremper Longman III, How to Read the Psalms (InterVarsity Press, 1998), p. 108. He cites his article, "A Critique of Two Recent Metrical Systems," Biblica 63 (1982):230-254.

[9] Kidner, Psalms 1-72, p. 2.

[10] George L. Robinson and Roland K. Harrison, "Isaiah," ISBE 2:904.

Copyright © 2026, Ralph F. Wilson. <pastor![]() joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.

joyfulheart.com> All rights reserved. A single copy of this article is free. Do not put this on a website. See legal, copyright, and reprint information.